Sorry about the silence. I have been busy. If you haven’t heard the news, my Hollywood career recently didn’t skyrocket. I have been not cast in Black Widow 2, and not rehearsing for this film now occupies the majority of my time. I can’t wait for you to not see me acting alongside Scarlett Johansson. The film’s script does not contain a sex scene between us, and Ms Johansson did not whisper that perhaps we could violate SAG-AFTA rules and perform it unsimulated, and I have not decided whether to not be lead by my head or my heart on this issue. Let’s talk about My Terrible Life by Sunny McCreary.

McCreary is a pen name of Michael Kelly, an online humorist who went viral in nineteen-ninety-$DATE with Roy Orbison in Clingfilm. These surreal vignettes describe German citizen Ulrich Haarbürste, who is a fan of rockabilly legend Roy Orbison, wrapping his idol in clingfilm.

It always starts the same way. I am in the garden airing my terrapin Jetta when he walks past my gate, that mysterious man in black.

‘Hello Roy,’ I say. ‘What are you doing in Dusseldorf?’

‘Attending to certain matters,’ he replies.

‘Ah,’ I say.

He apprises Jetta’s lines with a keen eye. ‘That is a well-groomed terrapin,’ he says.

‘Her name is Jetta.’ I say. ‘Perhaps you would like to come inside?’

‘Very well.’ He says.

Roy Orbison walks inside my house and sits down on my couch. We talk urbanely of various issues of the day. Presently I say, ‘Perhaps you would like to see my cling-film?’

‘By all means.’ I cannot see his eyes through his trademark dark glasses and I have no idea if he is merely being polite or if he genuinely has an interest in cling-film.

I bring it from the kitchen, all the rolls of it. ‘I have a surprising amount of clingfilm,’ I say with a nervous laugh. Roy merely nods.

‘I estimate I must have nearly a kilometre in the kitchen alone.’

‘As much as that?’ He says in surprise. ‘So.’

‘Mind you, people do not realize how much is on each roll. I bet that with a single roll alone I could wrap you up entirely.’

Roy Orbison in Clingfilm stories stick to your brain like leeches. Even if you don’t laugh, you also don’t forget. Taking a stab at why, it’s because they’re so specific.

Every detail is memorable. Ulrich Haarbürste (lit: “Hairbrush”) is a funny name. Germany (aside from 1933-1945 and some select periods before and after) is a funny country. Haarbürste’s writing is strange, possessing the grammatically correct yet “wrong” register of an educated man who has learned English as a second language. A terrapin is an unusual pet, and “Jetta” an incongruous name for one (cars are known for being fast, turtles are known for being slow.)

And although Roy Orbison is portrayed as a willing (if occasionally reluctant) partner in Ulrich Haarbürste’s games, the idea of a fan wrapping a celebrity in clingfilm is peculiar and evokes the behavior of the Bjork stalker (a psychosexual desire to possess and control and objectify). And at least Bjork is an attractive woman, while Roy Orbison—who achieved fame in the 60s, was stomped flat by the British Invasion, and then staged a latter-day comeback—was a weedy, gangly, jug-eared man (it was laughable whenever a photographer posed Orbison next to a sexy car: he looked like a Make-A-Wish kid whose dying request was to be James Dean.) Making him the target of Haarbürste’s obsession is yet another individualistic fingerprint in a crime scene full of them. Specificity = good. Genericity = bad.

Am I explaining the obvious? Probably, but it eludes most writers, who hate specificity like it murdered their puppy. It’s believed now that writing must be “relatable”: your story should be set in Anytown USA, starring a character exactly like the reader. No deviation is allowed: if you describe your hero as enjoying marmalade on his toast (so the thinking goes), you’ve alienated the book-reading section of the market that prefers jam on theirs. And since you cannot predict the tastes of nine billion people, the only solution is to write characters with no traits at all.

Think of Harry Potter. He has no personality. JK Rowling actually writes good characters most of the time: Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger are incandescent on the page, and even controversial later additions like Stepin Fetchit the House Elf, Shlomo Shekelstein the Goblin Banker, and the Trans Bathroom Molester are vividly memorable. Harry, however, is boring. He is not an interesting person, he is a person that interesting things happen to. I read the The Deathly Hallows‘s final chapter with a sense of embarrassment. “Wait, you think I care about Harry’s life after he defeats Voldemort?”

Online, we see too many attempts to recapture whatever Roy Orbison in Clingfilm had. Most fail, because they’re too general, too “relatable”, too Harry Potter. They take the form of “I’m a 20 year old boy with a hot sister and [something wacky happens]”. They cast too wide a net and lack the sting and punch of the particular. They do not contain terrapins called Jetta.

I was delighted to discover that Michael Kelly has a website (and book) full of Roy Orbison in Clingfilm stories. I was also delighted to discover that this is not his best work. Not by a long shot!

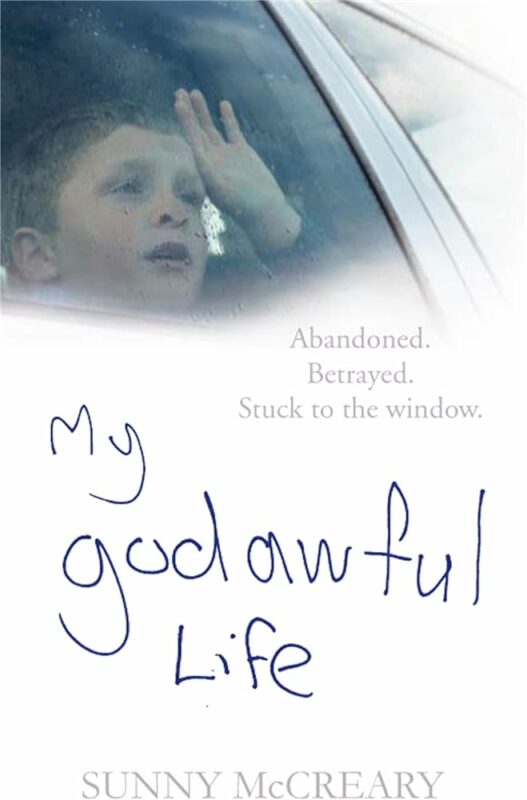

One of his many projects is My Godawful Life. Which I haven’t discussed at all.

Kept in a bird-coop by his parents, Sunny McCreary endured a childhood of neglect, abuse and being bullied by pigeons, only to find it was all downhill from there. In the course of the most painful life ever, he survived tragedy and maiming, a savage convent school education, being pimped out in pink-satin hot pants, a degrading addiction to helium, and having a baboon’s arse grafted onto his face. Then things got really bad.

This book is a parody of “misery lit” such as Dave Pelzer’s A Child Called It. These books, with their combination of luridly-described child abuse and sanctimonious hustle-positivity (“as my stepfather shoved my entire face into a woodchipper, I reflected that each day is a blessing from God”), provide a satirical target a mile wide, but what monster would mock the memoirs of abused children? The same monster who would wrap Roy Orbison in clingfilm, that’s who.

The book is so goddamn funny it’s unreal. It just keeps going and going and going. You’d think the joke would get played out somewhere around page zero, but it never does. Each chapter has a new outrage, a new horror, a new source of ridiculousness. The part where Sunny halfheartedly attempts suicide by jumping in front of parked cars and out of ground-floor windows.

Mr Kelly seems to have soured on the book. Which is a shame. It’s great!

[Edit, 2013: I repent this now, in fact I would pretty much like to forget I wrote it. It has moments of inspiration but it also has moments of the most appalling playground crassness. I would still maintain the things I was parodying are worse, but it crosses lines, sometimes with purpose but sometimes gratuitously, and what was bracing in the original five-page bit becomes wearing stretched to 300. Also, I wanted it to be more than a rag-bag of sick jokes, so it’s a rag-bag of sick jokes that develops delusions of grandeur.

What are these delusions of grandeur?

Well, midway through, Sunny adopts an autistic child with “Tourettes” called Euphemia. (I don’t exactly remember the circumstances: I’m reviewing this from memory because I gave my only copy away to a girl who has now moved far away from me for reasons which may or may not be related.) I find “genius child” tropes tedious, and was expecting and hoping for her to die. She doesn’t, and gradually mutates into arguably the book’s most vivid character.

Euphemia provides another source of comedy, but also acts as a foil to Sunny: pushing and provoking him to leave his shell. They fight a lot, but in the end form a good pair. Their interplay adds a lot of muscle and fiber to the book (which, I’ll admit, is mostly one note banged on a piano over and over.) The final couple of chapters are actually written by Euphemia, and basically address the phenomenon of misery lit head on, without a satiric voice. There is great evil in the world. But there’s also a force adjacent to great evil: a force that compels people to watch and stare and rubberneck at car accidents and enjoy outrage and misery. Suffering as entertainment. Is there something wrong with people who buy and read misery lit? Michael Kelly seems to think there is, and I would agree. It inspires the same revulsion in me as people who have sex with their furniture: even if the act itself isn’t wrong, enjoying it indicates there’s something wrong with the actor. The book might embarrass Kelly now, but it has only become more and more relevant, as this stuff continues to encroach into the mainstream.

No Comments »

Comments are moderated and may take up to 24 hours to appear.

No comments yet.